We were the odd ones out travelling independently in the Soviet Union in 1976. As far as I know, 1976 was only the second year that tourists were allowed to travel this way, but even then it was tightly controlled with an itinerary sanctioned by Intourist and constant monitoring.

This does not mean there weren’t many international travellers in the Soviet Union. In 1976 there were 3.9 million tourists, but the vast majority of these were from Soviet block countries, especially Poland and Finland. Only a few hundred thousand came from the West. Of these, the majority were classified as “mass tourists” who travelled on fully organised group tours, flying in to the country, moving between cites by bus or train, staying in tourist hotels, sightseeing only what was approved for them and escorted 24/7 by trained guides whose role was nothing short of indoctrination.

Another form of group travel was the delegation or the official visits. These were even more strictly supervised. If the visitors were pro-Soviet their tour set about confirming the glories of communism so that the visitors could return home and spread the good news. If they were not from pro-Soviet countries, it was hoped that they could be converted through their experiences or at least tell positive stories.

Another option was to take a study program, the most notable being six weeks of study of the Russian language with guided weekend travel at the Leningrad State University. This program still operates although it is now at St Petersburg State University, of course.

There was one other travel group: the “vodka travellers”. These were mainly Finnish travellers notorious for their misbehavior and revelry after sampling vast amounts of prized Russian vodka. We were too scared to be anything but well behaved.

We were certainly breaking new ground. Even our trusty travel guide “Let’s Go Europe” which generally encouraged adventure for its readers, recommended organised tours in the Soviet Union rather than a camping tour by car.

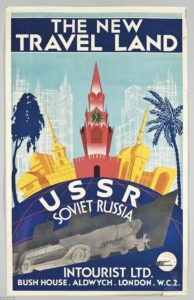

We went through a tedious bureaucratic process in London getting our visas and planning our itinerary from the state controlled tourist agency, Intourist, the official travel agency for the Soviet Union. It had been established by Stalin in 1929 and was originally staffed by KGB officials. Some wag claimed that Intourist was to tourism what indigestion is to digestion. I think I understood that by the time we had finalised our travel arrangements. We had to establish our itinerary before leaving England. The rules were clear:

- No deviation from the approved itinerary

- Travel on major roads only

- Arrive on time at our destinations

- Check in on our arrival

- Submit our passports to officials on arrival at each destination for return on our departure (Eek! That made me nervous!)

- Keep a record of all financial transactions (these are checked as you leave Russia)

- No photos of aeroplanes, military personnel or intallations (as if), airports, railway stations, factories and people at close range.

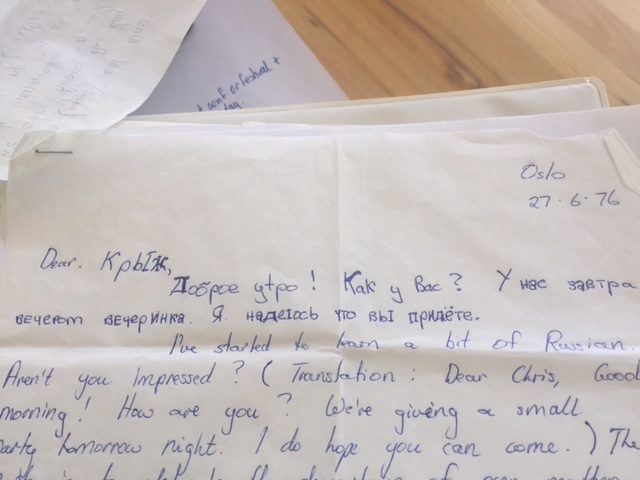

It was recommended that we know the Cyrillic alphabet in order to read road signs. This became my job and I did get the hang of it sufficiently well to get us through. Witness the opening to a letter home. (Readers of Russian are advised to skip this, or if you must, send me a corrected version.)

We were not able to drive very far before being checked at watchtowers positioned every 30-50 kilometres along the main roads. As we approached these, road signs indicated that we should slow down which we dutifully did. Presumably someone read our number plate as we drove past and checked it against their list of who should be travelling down that road on that particular day.

There is apparently an old saying that Russia has two problems: fools and roads. Our trip confirmed the latter. The roads were appalling and driving was positively dangerous. Our itinerary took us along so-called highways and generally speaking these were in a pretty parlous state, pot-holed and bumpy and with treacherous edges. Occasionally the bitumen would disappear and we would drive on gravel for a time. We could see that once off these highways we would be travelling on along dirt roads.

Most of the traffic was freight and military transport. Very few Russians owned their own cars. Petrol stations were few and far between and the quality of the fuel was highly questionable. We blamed the poor quality petrol for the engine seizing about six weeks later in France. The only compensation was that petrol was cheap – 45 cents per gallon. (In Poland it was $1.10 per gallon.)

Even today there are complaints about driving in Russia. A recent blog on a site about St Petersburg suggests that driving in Russia is for intrepid and adventurous drivers and that the journey by car between Moscow and St Petersburg is stressful and tiring. Little do they know!

Our first scheduled stop was Vyborg, 30 kilometres from the Finnish border and 174 kilometres from our destination for that day, Leningrad. At Vyborg we had to check in with the authorities and have our papers stamped. My memories of Vyborg are in shades of grey as if we had slipped into a black and white movie circa 1940. We drove through streets that were pot-holed, past buildings that were near to collapse and with walls pockmarked by gunfire. There were mounds of rubble out of which tufts of green grass were growing. It was over 30 years since the end of the war and here the ruin it caused was still visible.

Vyborg is located in a zone known as Karelia the ownership of which has been disputed between Finland and Russia for decades. Check out this interetsing video on the history of Viipuri, the Finnish name for Vyborg, if you want to know more. It is in Finnish, but has sub-titles (and quite marvellous music!)

We made our way to the Vyborg Railway Station, a grand building that had clearly survived the War although it was in its second iteration, the original building having been destroyed in the Continuation War with Finland.

We reported in at a desk downstairs just off the main plaza of the station where a young man in uniform sat shuffling with papers. He continued to do this as we stood there waiting. He then looked at us both, pushed back his chair with a scrape and indicated we should follow him. He lead us up to the first floor where he marched along a corridor open on one side and from which you could look down on the railway station plaza below. The other side was lined with offices which had half glass doors and smudged windows. Inside the offices the air looked dusty and the light was yellow. People were bent over at their desks. No one looked up at us as we went by. The only sounds were our footsteps and the noise from people down below on the plaza, but even that seemed strangely hushed, especially for a railway station.

We were taken into an office at the end of the corridor where a clerk snatched our papers from us, glared at our photos, checked them carefully against what he saw in front of him, muttered something in Russian, signed and stamped our papers and dismissed us with a flick of his wrist. We did thank him, but he was clearly not interested in our gratitude.

We were escorted to the front of the building in silence. All of that took under ten minutes. Once we were outside, our escort indicated that we should leave. He stood at the top of the steps and watched us walk to the Kombi van. As we started to drive away I turned and looked back. He was still standing there, alone and perfectly still, watching us as we drove away. We drove out of the station parking bays and away to the main road and he still stood there while I watched him until he disappeared from my view and we headed to Leningrad, our first overnight stop.

I am unsure how we came to decide on the details of our itinerary. Was there a limit to the number of days we were allowed to stay in one place? We had two nights in Leningrad which seems a ridiculously short time now. Perhaps too long a stay appeared suspicious.

Between Leningrad and Moscow we had two scheduled overnight stops, one at Novgorod and another Kalinin, now called Tver, but they were just places to sleep not to explore. We arrived in Moscow on July 13th and left four days later driving to Smolensk (398km) where we stayed for one day. On July 19th we went on to Minsk, now the capital of Belarus (330km), and the next day we drove out of the Soviet Union and into Poland via what was then the border town of Bialystok. Looking back I can see that for most days of this trip we were driving from one destination to the next. It is difficult to be precise about the journey because roads have changed and new highways and motorways have been built. I estimate that we drove approximately 2150kms in 12 days. That’s probably 50 checkpoints along the way!

And of course we did stray from our itinerary. We got lost. We got detoured and we could have got ourselves into serious trouble. More of that anon!

References

Auvo Kostiainen “Groups and delegates: Travel from Finland to the Soviet Union from 1950 to 1980″

Auvo Kostiainen “The Soviet Tourist Industry as Seen by the Western Tourists of the Late Soviet Period”

Let’s Go Europe 1976-77

Amazing, Margaret